To Train Leaders for the 21st Century, MIT Must Put Free Speech First

To Train Leaders for the 21st Century, MIT Must Put Free Speech First

A Post by FIRE’s Komi German

"Ever since the shooting of George Floyd, it felt like anything you said could be used against you, even if you had good intentions and even if you agreed with the protests, which is why I've decided to remain silent." – self-identified liberal male undergraduate MIT student, class of 2022

"As a recent immigrant from Europe, I was trying to explain how Americans do have a culture and that America isn’t ‘the most racist’ country, but ended up being called a racist ignorant bigot by my peers instead." – self-identified libertarian female undergraduate MIT student, class of 2023

“Whether in class or in the dorms, if you voice disagreement with the agreed upon liberal narrative you will be ostracized socially and targeted for being someone who uses 'hate speech.'” – self-identified conservative male undergraduate MIT student, class of 2021

Intolerance has become endemic across our nation’s institutions of higher education. Not even MIT, long-considered our country’s best engineering school, is immune. In 2021, the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education (FIRE) released its second annual College Free Speech Rankings (CFSR), based on the largest ever national survey of student attitudes toward free speech. From data on more than 37,000 undergraduate students at more than 150 two- and four-year colleges and universities across the country, FIRE’s CFSR survey reveals that the vast majority of students nationwide, including those at MIT, feel both uncomfortable expressing themselves and quite comfortable censoring others. Beyond that, several of MIT’s own policies may restrict a wide range of constitutionally protected expression, as we shall see, earning the Institute FIRE’s cautionary “yellow light” rating. MIT leadership urgently needs to teach and model protection of free speech if the Institute is to continue to deliver an exceptional educational experience.

Censoring Every Which Way: Both Self and Others

The CFSR survey contains data on 250 randomly selected MIT undergraduate students. The sample was 47% male, 51% female (and 2% other), aligning closely with the actual mix of 52% male, 48% female. In addition, among the MIT student sample, 60% considered themselves liberal and 15% consider themselves conservative. Similarly, 44% considered themselves Democrat, and 7% Republican.

The first finding from the CFSR survey is that a majority of MIT undergraduate students surveyed are often afraid to express their views, particularly on controversial topics. 70% of MIT students, compared to 61% of students across the country, feel “somewhat” or “very” uncomfortable “publicly disagreeing with a professor about a controversial topic.” Similarly, 54% of MIT students, compared to 42% of students across the country, feel somewhat or very uncomfortable “expressing disagreement with one of your professors about a controversial topic in a written assignment.” And 51% of MIT students, compared to 48% of students across the country, report being somewhat or very uncomfortable “expressing your views on a controversial topic during an in-class discussion.” Strikingly, 84% of MIT students, and 83% of students across the country, have at times felt unable to “express your opinion on a subject because of how students, a professor, or the administration would respond.” 17% of MIT students, compared to 21% nationally, said they have felt this way “often.” And MIT students who self-identified as conservative were nearly four times more likely than their liberal peers to report that they have at times felt this way often (45% vs. 12%).

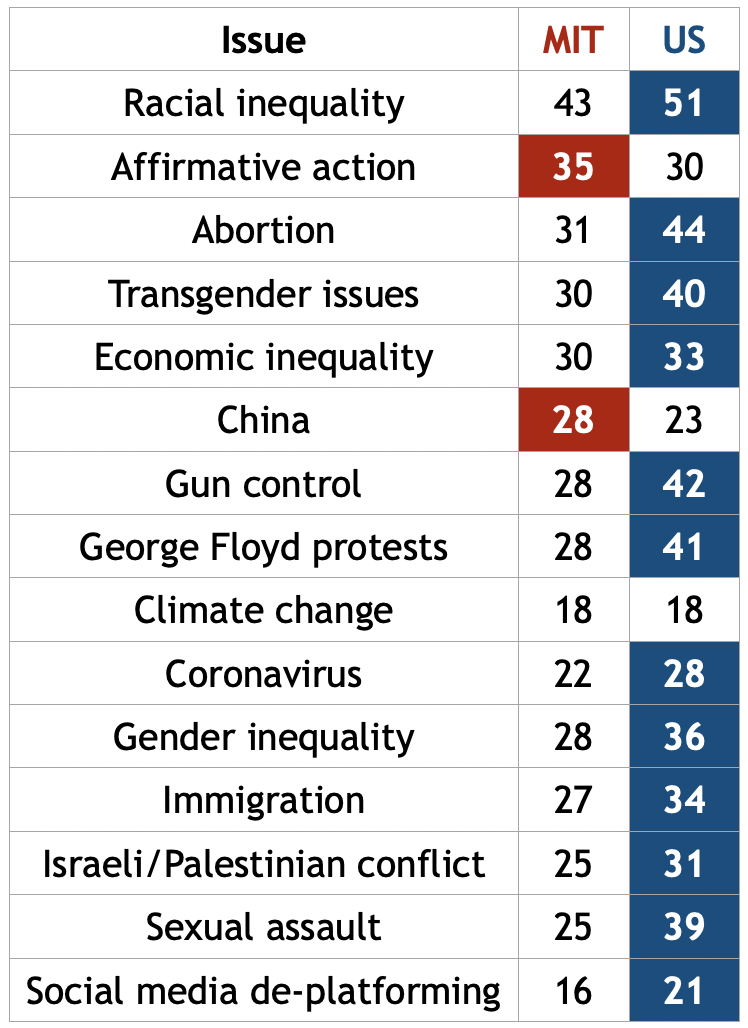

When asked about fifteen major social issues facing the country, MIT students identified racial inequality as a difficult topic to have an open and honest conversation about more often than any other topic (see table below). This was also the case for students across the country. Yet a higher percentage of MIT students than students nationwide found it difficult to discuss affirmative action (35% vs. 30%) and China (28% vs. 23%), suggesting that these two topics are particularly contentious at MIT.

Percentage of Students at MIT and across the U.S. Reporting Difficulty Discussing 15 Contentious Topics

Among MIT students, there were strong political differences in perceptions of the most difficult topics to discuss. Conservative MIT students were more likely than their liberal peers to report that it is difficult to have an open and honest conversation about all fifteen issues. Conservative MIT students were more than seven times more likely than their liberal peers to report that they find it difficult to discuss at least one of the issues. These political differences are slightly more pronounced among MIT students than they are among liberal and conservative students across the country overall. On the following issues, conservative MIT students were more than twice as likely as their liberal peers to report difficulty having open, honest conversations on campus:

· Transgender issues (65% vs. 26%)

· Gun control (58% vs. 23%)

· George Floyd protests (52% vs. 24%)

· Climate change (36% vs. 16%)

· Social media deplatforming (29% vs. 14%)

In addition, there were some strong gender differences in MIT students’ comfort discussing a range of issues. These differences were stronger than differences between male and female students across the country. Male MIT students were more than twice as likely as their female peers to report difficulty discussing immigration (46% vs. 19%) and social media de-platforming (25% vs. 12%). This finding is unique to MIT. Furthermore, across the country female students identified sexual assault as a difficult topic to discuss far more often than males did (42% vs. 34%), but at MIT only 25% of female students reported difficulty, compared to 35% of male students.

Many MIT students are afraid to express themselves, yet their survey responses reveal that they are not afraid to stop others from expressing themselves. MIT students are about as willing as the average student across the country to embrace extreme methods of censorship. 32% of MIT students, compared to 33% of students across the country, believe “shouting down a speaker or trying to prevent them from speaking on campus” is acceptable to some degree (4% “always,” 28% “sometimes”). In addition, 14% of MIT students, compared to 13% of students across the country, believe “blocking other students from attending a campus speech” is acceptable to some degree (1% “always,” 13% “sometimes”).

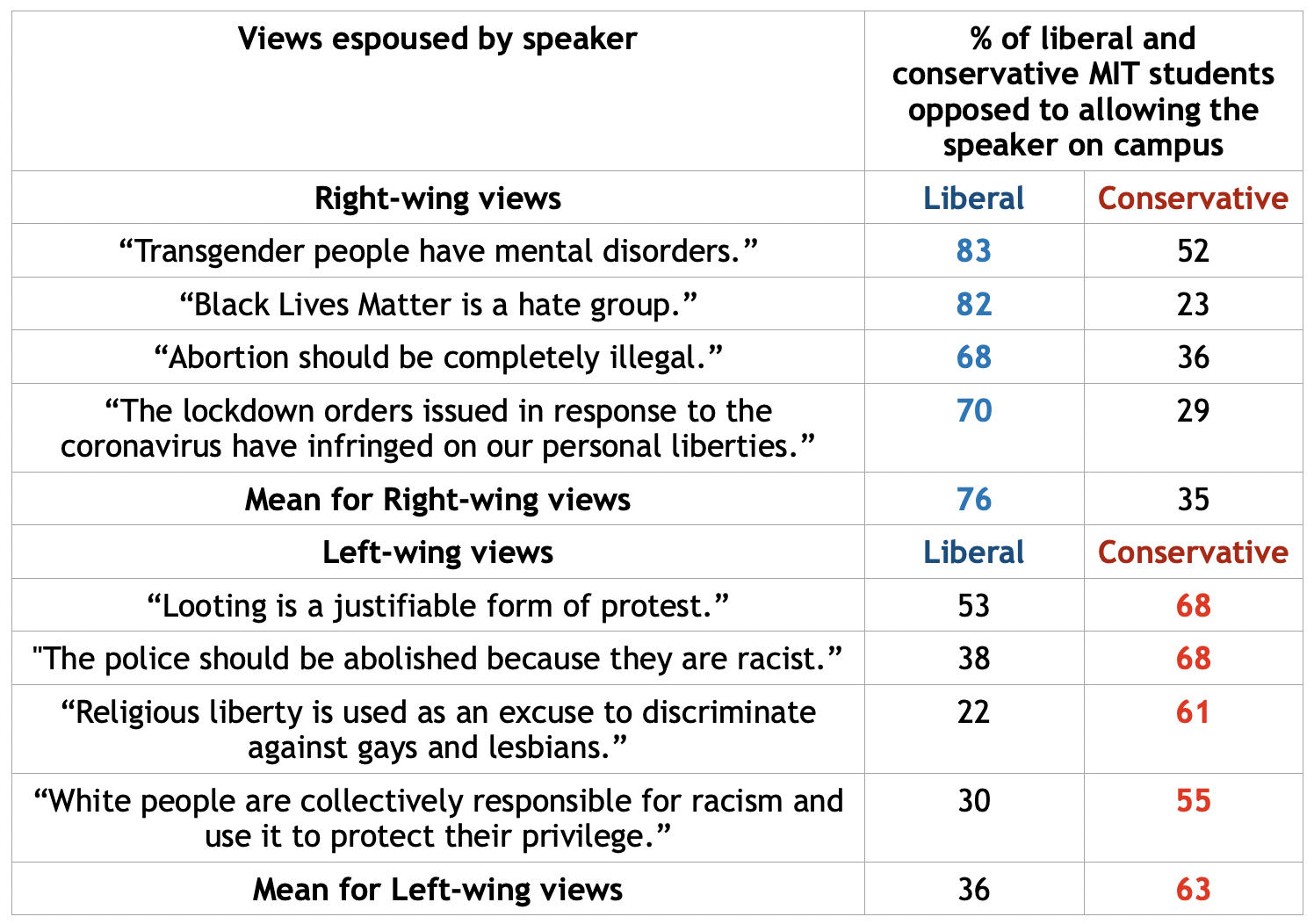

For the vast majority of US students, including those at MIT, censorship is political. When asked the extent that they would support or oppose the administration allowing on campus a series of hypothetical right- and left-wing speakers, more MIT students were opposed to allowing all four right-wing speakers on campus than were opposed to allowing any of the four left-wing ones. And female MIT students were more likely than their male peers to oppose allowing right-wing speakers on campus.

Political intolerance is not unique to left-wing MIT students. Both liberal and conservative MIT students report a high willingness to censor speakers whose views differ from their own. 83% of liberal MIT students “somewhat” or “strongly” oppose allowing a speaker on campus who promotes the right-wing idea that “Transgender people have mental disorders.” Similarly, 68% of conservative MIT students somewhat or strongly oppose allowing a speaker on campus who promotes the left-wing idea that “The police should be abolished because they are racist.”

The following table compares the percentages of liberal and conservative MIT students who somewhat or strongly opposed allowing speakers with various views on campus. The four mean scores reveal that, for these sets of views, liberal students are both 1) more willing to censor right-wing views than conservative students are to censor left-wing views, and 2) more willing to censor left-wing views than conservative students are to censor right-wing views.

Constitutionally Protected Expression May Not Be Protected at MIT

Given students’ tendency to self-censor and to endorse the censorship of others, it is crucial for university leaders to unequivocally commit to protecting free expression on campus. Yet MIT leadership either isn’t doing so or students are not receiving the message. Fully 33% of MIT students in the CFSR survey believe that the administration makes it “slightly” or “not at all” clear that it protects free speech on campus. Further, 30% believe it is “not very likely” or “not at all likely” that if a controversy over offensive speech were to occur on campus, the administration would defend the speaker’s right to express their views. MIT students who report greater self-censorship are far more likely to express these doubts about the administration’s commitment to free speech.

MIT’s speech policies suggest why students lack clarity regarding the administration’s commitments. The Institute’s inconsistent and ambiguous policies have earned it a FIRE speech code rating of “yellow,” meaning either that it maintains at least one policy that could be applied to suppress protected speech, or that clearly restricts a relatively narrow category of speech. In MIT’s case, it is the former.

“Yellow light” institutions like MIT are intermediate between “red light” institutions, which maintain at least one policy that “both clearly and substantially” restricts freedom of speech, and “green light” institutions, whose policies do not seriously threaten campus expression. A fourth rating, known as “warning,” is given to a private institution that “clearly and consistently states that it holds a certain set of values above a commitment to freedom of speech,” meaning that students do not have a reasonable expectation of free speech rights there.

MIT, unlike “warning” institutions, does promise students free speech rights, thereby binding it morally, and perhaps legally, to protect free speech. For example, MIT states that “freedom of thought and expression” is “essential to a university.” Students reading this statement would reasonably expect MIT to provide them with free speech rights commensurate with those of their peers at public institutions.

FIRE’s Policy Reform team rates each institution’s policies based on the extent to which it restricts constitutionally protected speech, applying the First Amendment standards governing the area that particular policy regulates. As policies regulating expression vary greatly, from regulations on content posted in residence halls to restrictions on when and where students can protest, they cannot readily be scored quantitatively. Instead, the team determines whether the policy restricts protected speech and whether that restriction is substantial or narrow, as well as clear or vague.

Public colleges and universities perform better on free speech than do private ones. Of all 481 public and private schools reviewed in FIRE’s 2022 Spotlight on Speech Codes report, 12% were rated “green,” 68% “yellow,” 19% “red,” and 2% “warning.” By contrast, of the 107 private colleges and universities reviewed, 4% were rated “green,” 51% “yellow,” 41% “red,” and 5% “warning.” If MIT became one of the 4% of private institutions to be rated “green,” this triumph would win widespread praise from FIRE, from the American Council of Trustees and Alumni (ACTA), from the MIT Free Speech Alliance, from the Alumni Free Speech Alliance, from Heterodox Academy, and from a growing number of thought leaders across the country who have raised concerns about free speech restrictions on campus.

Four MIT “Yellow Lights” …

At present, MIT has four “yellow” policies, including harassment, sexual misconduct, internet usage, and even freedom of expression. The MIT handbook states that “freedom of expression is essential to the mission of a university.” This is laudable. However, it immediately includes a caveat: “So is freedom from unreasonable and disruptive offense.” MIT discourages students from “putting these essential elements of our university to a balancing test.” This indicates that administrators will be weighing students’ free speech against the interest of avoiding “disruptive offense,” and may infringe on protected speech in order to prevent such offense. Therefore, it is crucial for MIT to explain that although the Institute is committed to promoting civility and respect, in instances where an individual engages in expression that is widely seen as offensive but is protected by the First Amendment, such expression will be protected.

Yet too often, the MIT administration has expressed its support for free speech, only to immediately add that concern about the psychological harm of speech will be considered in ways that may restrict the rights of the speaker whose words have allegedly caused the harm. We see this language in MIT President L. Rafael Reif’s letter to the MIT community titled, “Reflections and a path forward on community and free expression,” in which he explained [emphasis added]:

“Freedom of expression is a fundamental value of the Institute…This commitment to free expression can carry a human cost. The speech of those we strongly disagree with can anger us. It can disgust us. It can even make members of our own community feel unwelcome and illegitimate on our campus or in their field of study. I am convinced that, as an institution, we must be prepared to endure such painful outcomes as the price of protecting free expression – the principle is that important.

I am equally certain, however, that when members of our community must bear the cost of other people’s free expression, they deserve our understanding and support. We need to ensure that they, too, have the opportunity to express their own views.”

President Reif is correct to defend free speech so emphatically. But in disinviting geophysics Professor Dorian Abbot over an op-ed critical of diversity, equity, and inclusion initiatives, as I discussed in the FIRE piece, “What does MIT stand for? Faculty, alumni want answers,” MIT did exactly the opposite. “Besides freedom of speech, we have the freedom to pick the speaker who best fits our needs,” said MIT Earth, Atmospheric and Planetary Sciences (EAPS) department chair Robert van der Hilst, who disinvited Abbot. “Words matter and have consequences.” Evidently, MIT determined that an op-ed advocating for “Merit, Fairness, and Equality (MFE) whereby university applicants are treated as individuals and evaluated through a rigorous and unbiased process based on their merit and qualifications alone” constituted “unreasonable and disruptive offense.”

How can Schumpeterian creative destruction, and the resulting innovation for which MIT is justly famous, thrive when offense is so easily taken?

… Including Two Policies of Questionable Constitutionality

MIT also maintains two harassment policies with definitions of harassment that fail to fully adhere to the Supreme Court’s peer hostile environment standard from Davis v. Monroe Board of Education (1999), which restricts only conduct that is “so severe, pervasive, and objectively offensive, and that so undermines and detracts from the victims’ educational experience, that the victim-students are effectively denied equal access to an institution’s resources and opportunities.” As a result, MIT’s policies could too easily be applied to restrict speech that is viewed as harassing or offensive, but that does not actually meet the legal standard for harassment.

The “Policy on Harassment” provides a list of examples that “would likely be considered harassing,” and the “Sexual Misconduct” policy provides a list of conduct that “might be deemed to constitute sexual harassment if sufficiently severe or pervasive.” These lists include broad examples like “sexually explicit jokes” and “displaying sexual objects, pictures, or other images,” which may indeed be a part of a pattern of conduct that constitutes harassment, but when standing alone (even when “severe or pervasive”) are typically constitutionally protected. To improve these policies, MIT should tie any listed examples back to the full definition of harassment to make it clear that speech is only punishable when it is a part of a pattern of conduct meeting that definition.

Institutional Risks of Not Protecting Free Speech

A campus targeting incident is an effort to investigate, penalize or otherwise professionally sanction a scholar for engaging in constitutionally protected forms of speech. FIRE’s Scholars Under Fire database documents the ways and reasons that scholars have faced calls for sanction; how scholars and institutional administrators have responded; and what sanctions, if any, scholars have faced as a result.

Across the country, when universities prioritize protection against psychological harm over protection of free speech, thereby forgoing legal considerations, they avail themselves to the myriad demands for arbitrary professional sanctions documented in the Scholars Under Fire database. In the examples here, here, here, here, here, and here, targeting incidents occurred because “suggestive comments” and “sexually explicit jokes” were considered sexual harassment, even though those expressions did not meet the legal standard for harassment.

When institutions do not adhere to clear legal standards, even expression that is entirely accidental can be grounds for punishment. John Peng Zhang, an assistant professor of business at the University of Miami, was terminated for sharing with his Zoom class a screen that unknowingly included a pornographic bookmark tab. MIT considers “displaying sexual objects, pictures, or other images” to be an example of sexual harassment, so just such a sanction, however unwarranted, could well be invoked at MIT.

Also concerning is the section of MIT’s internet usage policy that prohibits “Any use that might contribute to the creation of a hostile academic or work environment.” This allows administrators to apply the policy against speech they subjectively find “might” create a hostile environment, but that does not do so, such as speech that is viewed as hostile or offensive, but that does not constitute unlawful hostile environment harassment.

MIT understandably wants to deter speech that unreasonably interferes with education or work. At other universities, however, numerous scholars have been accused of creating a “hostile environment” for expression that was not even directed at a particular student or group of students, but instead was designed for pedagogical purposes, scientific inquiry, or to protect due process. Based on MIT’s policy language, each of these targeting incidents and professional sanctions that resulted from them would have been justified at MIT.

And at MIT, Abbot’s disinvitation was not the only time the Institute appeared in the Scholars Under Fire database. In 2019, Richard Stallman, who created the groundbreaking GNU Project and the subsequent Free Software Foundation in the mid-1980s at MIT’s Artificial Intelligence Lab, was forced to resign due to backlash “over a series of misunderstandings and mischaracterizations.” His offense? In an email about MIT’s ties to Jeffrey Epstein, Stallman asserted that it is an “injustice” to use the word “assaulting” to describe the conduct of deceased MIT professor Marvin Minsky, who allegedly had sex with one of Epstein’s trafficking victims. Stallman explained that he believed the available evidence and testimony did not make clear Minsky’s knowledge of coercion or culpability. Rather than issue a public statement reiterating its educational objective to develop the habits of mind necessary to “deal constructively with the issues and opportunities of our time,” MIT offered no public comment.

When faced with another political email controversy the following year, MIT leadership again failed to defend the targeted scholar. In 2020, Rev. Daniel Moloney was forced to resign from his position as Catholic chaplain because MIT students filed complaints to administrators (including the Bias Response Team), over an email about George Floyd. In the email, Moloney argued that we do not know definitively whether racism was responsible for Floyd’s death. Nelson, MIT’s vice president and dean for student life, called Moloney’s comments “deeply disturbing,” explaining that “by devaluing and disparaging George Floyd’s character, Father Moloney’s message failed to acknowledge the dignity of each human being and the devastating impact of systemic racism.”

In Its Approach to Diversity, MIT Compromises Academic Neutrality

The University of Chicago’s now classic 1967 Report on the University's Role in Political and Social Action (known as the Kalven Report) explains why institutions of higher education are obligated to remain neutral on social and political issues:

“The neutrality of the university as an institution arises then not from a lack of courage nor out of indifference and insensitivity. It arises out of respect for free inquiry and the obligation to cherish a diversity of viewpoints.”

Although some may see it as a sign of callousness and perhaps privilege for the university to remain neutral when it comes to the most contentious social issues of our time, the University of Chicago, long hailed as a stalwart defender of free speech and academic freedom, sees this neutrality as crucial to ensuring institutional legitimacy.

Yet MIT’s diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) training (excerpts here and here) instructs and quizzes students about power, privilege, and oppression, then concludes by urging students to engage in political action. The training is not optional: in the fall of 2020, MIT emailed all current and incoming students informing them that if they didn’t complete the widely criticized course, they would be unable to register for spring classes. Such policies and practices are precisely what the Kalven Report cautions against. Because the mission of the university is “the discovery, improvement, and dissemination of knowledge,” it “cannot take collective action on the issues of the day without endangering the conditions for its existence and effectiveness.” What if an MIT student disagrees with MIT’s approaches to diversity, equity, and inclusion? How does MIT reconcile the conflict between embracing DEI and respecting freedom of speech and conscience?

These questions apply not only to MIT students, but to faculty and staff as well. According to the “MIT Five-year Strategic Action Plan for Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (2021-2026),” all faculty participating in graduate admissions decisions, all Principal Investigators (PIs) who make postdoc hiring decisions, all hiring members on staff searches, and all faculty participating in faculty search committees will undergo MIT’s DEI training.

Promoting Personal Development by Protecting Free Speech

Balancing commitments to emotional well-being and free speech is hard. Constitutionally protected expression may discomfort students. When institutions commit to protecting free expression, they are asserting that the benefits of free expression in the long run outweigh the unpleasantness experienced in the moment.

Adopting such a position today is as important as it is difficult, given the high levels of social unrest our nation has witnessed in recent years. Yet new ideas and the exchange of ideas are key to the innovative economy and economic growth. Innovation is often described at the level of the country or institution, but as MIT students, faculty, and alumni are well aware, innovation actually occurs locally, at the individual level.

Although much of the speech that offends MIT students is unlikely to be the type of speech that leads to innovation, restrictions on such speech can reduce the likelihood of engaging in challenging discourse more broadly. After all, conversations that question our assumptions are inherently uncomfortable and lead to unknown places. In a campus community that values respect and civility, people ought to be sensitive to others; however, the subjectivity of what’s deemed offensive makes it difficult to be certain that one won’t inadvertently cause offense. And if the consequences of causing offense are severe enough, that risk, no matter how small, can easily discourage open dialogue on any issue.

Attempts to restrict offensive speech may seem benign, even beneficial; but campus penalties for offensive speech create a chilling effect on all speech. As Supreme Court Justice Anthony Kennedy stated in Ashcroft v. Free Speech Coalition (2000): “The right to think is the beginning of freedom, and speech must be protected from the government because speech is the beginning of thought.” In this way, free speech is not an end in itself; instead, it is a means to the development of mental faculties that allow individuals to reach their full intellectual potentials. To remain a national leader in innovation, MIT must state unequivocally its commitment to the free exchange of ideas. And we all must encourage MIT to do so, for we need the Institute’s brilliant minds to continue making discoveries that improve standards of living and quality of life for people across the country and the world.

Action Steps for MIT Leadership

-

Offer seminars and orientation programs that teach incoming MIT students the value of free speech and the principles behind the First Amendment. FIRE, in partnership with New York University’s First Amendment Watch, has developed a series of free-to-use modules, videos, and other resources that MIT’s First Year staff can incorporate into the Institute’s Orientation Program.

-

Adopt a free speech policy statement in the model of the Chicago Statement, which signals to faculty, students, alumni, and the public that freedom of expression supersedes freedom from expression. Since the Chicago Statement was released in 2015, over 80 institutions, including 13 of the schools ranked in the top 25 of FIRE’s College Free Speech Rankings, have publicly committed to free speech in this way.

-

Remove vague, subjective language in the harassment, sexual misconduct, internet usage, and freedom of expression policies that earn the Institute a yellow light rating. FIRE’s Policy Reform team is happy to work directly with the MIT administration to revise these policies.

-

Create and implement a five-year strategic action plan for free speech that aims to (a) understand the reason(s) MIT students are afraid to express their views; (b) increase MIT students’ tolerance of people whose views they oppose; (c) create opportunities for positive interactions between MIT students with different views; and (d) encourage students to resolve among themselves those interpersonal disputes that involve constitutionally protected expression, rather than seeking institutional inventions.

MIT: Seeking Excellence

In 2021, MIT ranked 76 out of 154 colleges and universities surveyed in FIRE’s College Free Speech Rankings. In no other realm of excellence would MIT tolerate such a mediocre ranking. If MIT fails to inculcate the value of free speech and commit unequivocally to its preeminent importance on campus, the Institute will remain vulnerable to the predations of mob rule and cancel culture. After all, despite attending one of the world’s most innovative institutions, many MIT students hold the same regressive, censorious beliefs as their peers who have caused the vast majority of scholar targeting incidents across the nation.

Soon the next MIT scholar will step outside the ever narrowing Overton Window, leading students and others, unaware of why the First Amendment exists, to demand that the Institute protect them from “unreasonable and disruptive offense.” With unequivocal commitment to protecting free speech and academic freedom, MIT, often viewed as the world’s best university, can ensure that each student develops the “versatility of mind” needed to achieve and succeed in the 21st century.